Soviet summer camp, Trump voters, and me

Why I'm reframing the way I think about (some of) my fellow citizens

A few months ago, I wrote about two of the three realizations/resolutions I came to in the wake of the presidential election regarding how I want to move through this next Trumpian epoch.

One of those realizations is that I need to be very judicious about how much political content I consume. So if you feel the same, and don’t want to read this post—which is political—I get it! Here, read something fun and apolitical instead! Or check out some of my latest book recommendations! See you next time!

Great. Hi, those of you who stayed. Thank you for indulging me.

I put off writing about this realization because it’s messy and complicated and multifaceted and because it’s taken me a while to fully articulate it to myself. I’m still trying to articulate it, I guess. Here goes.

Let’s start with an anecdote, because those are always fun.

In the summer of 1988, I went on a goodwill trip to the Soviet Union, in its twilight, in memory of Samantha Smith. She was the ten-year-old girl from Maine who wrote a letter to Yuri Andropov expressing her fears of nuclear war, and confusion over what she perceived to be the goal of the Soviet government. (And died tragically in a plane crash just a few years later.) An excerpt from her letter:

Why do you want to conquer the world or at least our country? God made the world for us to share and take care of. Not to fight over or have one group of people own it all. Please lets do what he wanted and have everybody be happy too.

Andropov replied, and extended an invitation to Samantha and her family to visit the Soviet Union to see that “In the Soviet Union, everyone is for peace and friendship among peoples.”

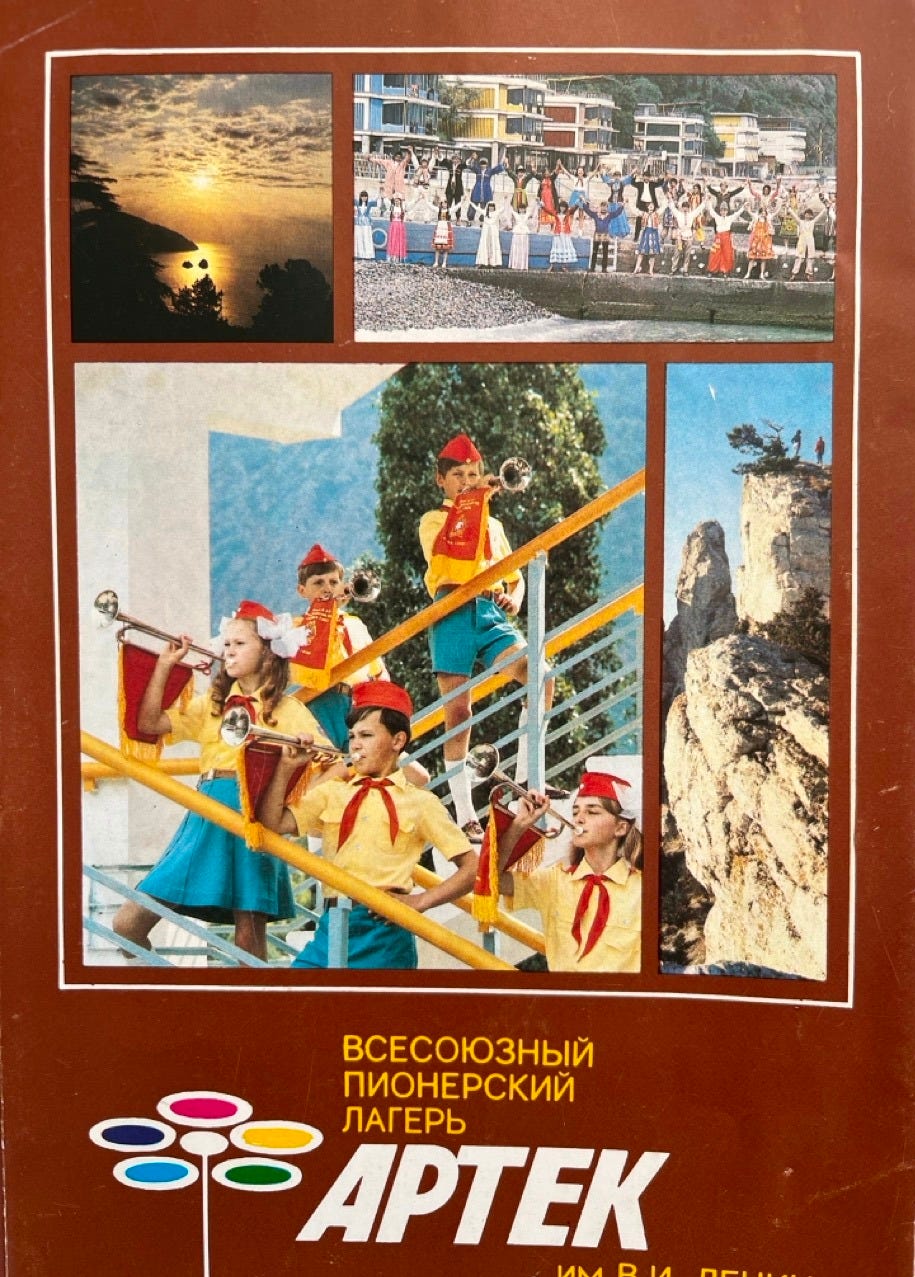

I spent a month at one of the places Samantha Smith visited on her tour: A Young Pioneer summer camp in Ukraine, on the shores of the Black Sea, called Artek. It was beautiful and extremely foreign-feeling and the kids we met there were absolutely lovely: welcoming, funny, playful. They were intrigued by our little group of Americans, and eager to ask us, in their very minimal English, if we liked Michael Jackson and say words like “Mickey Mouse” and “McDonalds.” The counselors were equally kind, if slightly less obsessed with random bits of American culture.

Half the time, we didn’t know what was going on. We let ourselves be shuttled from activity to activity—taking hikes and field trips, playing Sniper (a more aggressive form of dodgeball), singing songs, working in the dining hall, learning dances, competing in the Artek Olympics. I tried to qualify for the 100-meter sprint, but I was up against some serious, State-supported athletes, wearing the only sneakers I’d brought—a pair of white Keds (obviously). So instead, I was assigned to something translated to me as “The Jolly Games.” This consisted of various absurd relay races, many of which involved hula hoops. Sure, OK, great! Said 14-year old me.

But amidst all the wholesome fun, we never forgot that we were in an autocratic country. There were loudspeakers throughout the camp that periodically broadcast patriotic music and exhortations, and everywhere there were statues and mosaics of Lenin, hammers and sickles, and various scenes of communist bliss. (Happy children in their Young Pioneer uniforms! Beautiful factories! Amber waves of grain!).

The pièce de resistance and focal area of the camp was the amphitheater—again, Lenin everywhere—which was the site for morning calisthenics (in too-tight t-shirts and shorts that had probably been in circulation since the late 70s), performances, games, dances, and many, many patriotic rallies and ceremonies.

It was those rallies where the cognitive dissonance kicked in: All these kids who, an hour before, we were having seaweed fights with on the beach, were now in their dress uniforms, saluting and marching and carrying flags, celebrating the virtues of a country that we—GenXers growing up on movies where the Russians were the enemies and music videos where nuclear war was 99 balloons away—were pretty sure was the “evil empire.”

It was difficult to wrap one’s brace-faced, badly permed head around.

And then there the speeches—so many speeches!—usually delivered by fellow campers. We had an interpreter, Masha, assigned to our delegation, who translated things for us—mostly information about activities, or instructions from our counselors. (Russian friends who grew up in the USSR have since told me that Masha was almost definitely KGB.) But she stayed relatively quiet during the speeches.

We got the gist of them; they seemed to be mostly about the glory of communism and the beauty of the fatherland, the desire for peace and friendship throughout the world, blah blah blah. At one point, during a particularly fiery oration by a boy who couldn’t have been more than twelve, I asked Masha to translate in more detail. She smiled a little sheepishly. “You don’t want to hear this,” she said. “He is saying criticism about the United States. About Vietnam and imperialism and such.”

Now, I didn’t know much about geopolitics at the tender age of fourteen. But what I’d gathered about the Vietnam War was that 1.) In retrospect, most people agreed it was fruitless war that the US should never have waded into 2.) It was about preventing the spread of communism / Soviet influence, not about us being imperialists.*

Also, screw that kid! I knew that America had its faults and had made some mistakes, but we were the good guys! We totally saved Europe (including Russia!) in World War II! We had freedom of speech, freedom of the press, the freedom to protest! And Michael Jackson! And jeans! (Which many a camper wanted to buy off of us.) Didn’t they all secretly want to be us?

Maybe some of them did. But no doubt many bought into the officially sanctioned Soviet narrative—that America was a land of greed, depravity, and imperialism, and the USSR was the place to be. (And pay no attention to your neighbor who was shipped off to a gulag for saying something against the government. And don’t ask why so many writers and intellectuals and Jews try to defect.)

But after the speeches and ceremonies were through, it was right back to seaweed fights on the beach and Sniper games in the square. Back to giggling in broken English about which boys were cute. Back to “do you like the Beatles?” (“Girl” and “Michelle” were big hits on the Artek speakers. Maybe because the melodies are vaguely Russian-sounding?)

I took a lot of lessons away from my brief sojourn in the USSR. The biggest one was the classic “We are all much more alike than we realize.” But close behind was: Damn. People around the world are living in vastly different realities depending on stories they’ve been told—by their government, their religion, their culture, their statues in the square.

I was fascinated and flabbergasted by how we humans could have so much in common and yet see things so completely differently. In fact, I can probably trace my choice to major in cultural anthropology in college back to that trip. Maybe even my interest in writing fiction. I’m drawn to the challenge of trying to see the world through other eyes. And I like to think that the practice makes me a more empathetic person than I would be otherwise.

Here’s the thing, though: That sort of fascination with varying worldviews is easy in the abstract, when you’re not living side by side with folks whose lens on the world is so drastically different from your own. It’s a lot harder when you’re sharing a country with them. (Much less an immediate family—something I fortunately don’t have to deal with.)

The first time Trump won, the big wake-up call for me—and for a lot of liberals—was just how many people were willing to overlook, excuse, rationalize (and, in some cases, outright embrace) Trump’s racism, sexism, bullying, anti-democratic impulses, and, um, tenuous relationship with the truth.

For many folks, those things weren’t dealbreakers if it meant that their taxes might be lower or abortion rights would be rolled back further or that, quite simply, a Democrat would not be in the White House.

What I found harder to swallow this time around is that this is still the case—even after eight years of seeing what Trump is all about. I mean, the guy tried to overturn the results of an election, for God’s sake. Yet millions of Americans still think he was a better choice than Kamala Harris.

But while some liberals are quick to say that it’s because all of those millions of Americans are stupid / racist / misogynistic, I think that’s a vast (and unfair) oversimplification—not to mention one that makes Trump supporters dig in their heels.

I very much related to what George Saunders wrote in a recent Substack post:

I am trying to maintain two ideas at once: 1) Most people who voted for Trump are nice people. (I know this because many close friends and family members voted for him and, well, more than half of voters did), and 2) Our democracy really may be in peril. Trump has repeatedly said things to indicate this and people who worked closely with him the first time have said this.

So, what I’m trying to figure out is: how do the people who voted for Trump, some of whom I love, not see what I see in him? And, also, importantly: what am I not seeing, about the way the world looks to them? I'm not saying that the way they see it is right – I feel very strongly otherwise - but I am saying, or accepting that, yes, it really does look that way to them.

Me too.

But there’s another part of the story that Saunders doesn’t get into, and it’s the part I’m more tuned into this time around, because I’m more aware of how integral it is to Trump’s success: millions of very nice, smart Americans are living in a narrative that is at odds with actual, empirical truth. They are seeing a sanitized, carefully curated version of Trump, and a distorted view of reality.

If your response to this is “yeah, no kidding” please feel free to skip to the paragraph below the picture of Chris Pine.

Here are some facts: Crime is not increasing in America. Rather, crime rates continue to decrease steadily. Undocumented immigrants are no less likely than the general population to commit crimes—in fact they’re less likely to do so. (Related: Haitian immigrants in Illinois are not eating cats and dogs. Sorry, I don’t have proof, but trust me.) Yes, people did die during the January 6 insurrection and its immediate aftermath. Vaccines do not cause autism. Gender affirming surgeries are almost never performed on minors. The climate is definitely changing due to human activity. Also, Chris Pine is way hotter than Chris Pratt or Chris Hemsworth.

All of the above, except maybe the Chris part, would come as news to millions of Americans. Is it because they’re all stupid and gullible? Some of them probably are. (As are some non-Trump supporters.) But I don’t think most liberals, particularly those of us ensconced in our blue state, NPR-listening, New York Times reading bubbles, realize just how influential right-wing news, propaganda, and misinformation are in this country.

Huge numbers of people now get the bulk of their information online and/or places like Fox News and Newsmax. Many Trump voters get their information chiefly from friends and family, and/or don’t follow traditional news sources. The less attention people pay to political news, the more likely they were to vote for Trump in 2024. And among Trump voters who *do* follow political news, Fox is their #1 source. (Fox is also the #1 cable “news” network nationwide.)

Are there lies and misinformation coming from the left? Sure. But not nearly to the same extent or with the same reach. Meanwhile, it’s right-wing platforms that have the backing of billionaires, and right-wing media companies that have been buying up (and then often getting rid of) local and regional newspapers for years.

The right is, of course, also getting lots of help from our adversaries in Russia and elsewhere. More than once I’ve wondered if some kid I ran through hula hoops with during the Jolly Games or cleared dishes alongside in the dining hall is working in a troll farm somewhere, posting right-wing memes and picking fights with people on X.

So, here’s the upshot (finally!): While there are many people who voted for Trump for reasons I find abhorrent, and while I will always struggle to understand how so many people can overlook the repugnant things he says, the fascist-y things he pledges to do, and his overall character and temperament, I have also internalized the fact that millions of my fellow citizens are simply not seeing the same Trump, or the same world, that I am seeing. So, I can’t necessarily judge their choice to vote for him by the same criteria I’m using to vote against him.

And I don’t want to go through the next four or forty years feeling angry at and disdainful of millions of my fellow citizens. It’s just too toxic—emotionally, psychologically, and spiritually.

To be clear: This is not a “can’t we all just get along?” post. I can’t “just get along” with people whose values are fundamentally different from my own on certain issues. And I have no desire to “get along” with the extremists and unabashed bigots. As for the wealthy people and broligarchs who know exactly who Trump is but only care about their portfolios and their bottom lines—fuck those people.

I’m talking about the good and intelligent folks who are being manipulated, cut off from truths that might change the way they see things.

It’s worth reading this recent Substack post from the wonderful Rebecca Makkai, who is currently working on a novel set in 1938. An excerpt (boldface mine):

Something I’ve had to accept, in researching and writing this book, is that many of the people who fell for fascism in the 1930s were neither inherently evil nor idiots. They were deeply misinformed, and therefore manipulable.

One reason it’s so, so important for us to realize this: Otherwise, people who know themselves not to be evil, and not to be idiots, will assume they are too good and too smart to fall for the manipulations of narcissistic leaders. Many good and smart people saw through Hitler, but many good and smart people also fell for it all.

The internet helps us live in tiny information villages. It feeds people a far greater quantity of propaganda than was available in 1930s Europe. And as anyone who’s ever tried to get through to a conspiracy-believing uncle on Facebook can attest, it’s nearly impossible to convince someone that what they’ve been reading online isn’t true.

One reason people were so susceptible to propaganda in the 1930s was that it was based in unprecedented advances in both communications technologies (radio, film, cheaply produced printed material and posters) and advertising. Otherwise intelligent people were not equipped to filter out information as potentially manipulative. Similar things have happened in the past 20 years: Older generations used to taking TV news and official-looking printed matter as legitimate do not have the framework for understanding Fox News as propaganda. Younger people have a hard time resisting internet wormholes because we have not, as a species, figured out ways to resist the manipulations of overwhelming bias confirmation.**

To campaign online, to debate online, to try to spread facts online, is to pit ourselves against a tide of so much misinformation that we don’t stand a chance.

She goes on to offer some suggestions as to how those of us who see the danger of Trumpism to our country might fight back against that tide of propaganda and misinformation. I confess, I’m not too optimistic about our chances of victory. But here’s hoping.

In the meantime, I’ll be here continuing to focus on the causes that matter to me; on making and consuming art; on taking political news in small doses; and, finally, on remembering that the real enemy is not really the people who support Trump (not most of them, anyway); it’s Trump himself, and the false narratives and craven corporate interests that have ushered him into power.

I’ll be thinking about about all those sweet, seaweed-slinging, Michael-Jackson-loving Soviet kids I met in ‘88 who had been told all their lives by an oppressive, autocratic government that America was a capitalist hellscape, and the Soviets were the ones who were all about peace, friendship, and understanding.

Those Soviet kids were my friends. They were lovely. And we were all much more alike than we’d realized.

All posts on this non-imperialist Substack are free and publicly available, but writing is how I make my living. If you enjoy my writing, please consider upgrading to a paid subscription ($5/month! Cheap!), buying my book, or using this link when you buy any and all books, so I get a little somethin-somethin’ on the back end, and so independent bookstores get your bucks instead of Bezos. Thank you!

* There are certainly arguments to be made that the U.S. is a wee bit imperialist. I didn’t know as much about that at 14. Nevertheless.

** This bias confirmation stuff definitely happens on the left, too. It’s hard not to silo onesself, given the way algorithms work. (Algorithms that are, of course, designed to maximize engagement and therefore revenue.)

I have read other things that say much the same thing and I always fin d myself with unanswered - or maybe unanswerable - questions. I’ll pose just one here. Yes, people are feeding on mis- and disinformation that grossly distorts reality. Sure. But you don’t, I don’t, and half the country doesn’t. What is it that makes us different? Are we just feeding off a different source of mis- and disinformation? I’ll admit that’s possible, but I don’t think so. Some of us see the world for what it is, others see the world for what they want it to be and good old confirmation bias takes them the rest of the way. If misinformation was as powerful as you suggest then we too would be victim to it. Ask yourself why even in the USSR there were dissidents, what were they able to see that others weren’t? I won’t go on, but I’ll finish with this: what about us? Why is it always we who are trying to understand and kinda-sorta empathize with a deranged half of the country? Do you think for a second they’re doing likewise? Who speaks for us for a change?

This is the most extraordinary essay I’ve read in a long time. I devoured every single word. It’s so much of the nuance that we talk about around the dinner table, but is in short supply in the public conversation. Bookmarking, sharing, will probably come back to read again later. Thank you Jane, for your brain and your heart.