Well, after three years of a glorious, Covid-free existence, that little bloated Koosh Ball of a virus has caught up with me. (Fortunately, my version just feels like a cold.) I’m semi-confined to the third floor of our house, which is where my office is. So, when I learned about the death of C. Michael Curtis yesterday, I made a beeline for my desk, scattering tissues in my wake. I opened the file drawer and dug out my big fat folder of rejection letters from way back when, to find the ones that he had sent me.

For decades, Curtis was the fiction editor at The Atlantic, which used to publish a short story in every issue. Back in the early 2000s, when I was just starting to write fiction, I sent the magazine a few of my extremely mediocre stories. This was in that bygone time when we spelled email “E-mail,” and submitting stories meant sending actual manuscripts, on actual paper, in actual manila envelopes, accompanied by a SASE. (That’s a self-addressed, stamped envelope, for my daughter and the six other people under 35 who read this Substack.)

Most publications sent rejections in the form of photocopied form letters and slips. If you were lucky, you’d get a little handwritten note at the bottom, saying that the story came close to being accepted, or that they hoped you would try again. It was extremely rare to get personalized feedback about your work.

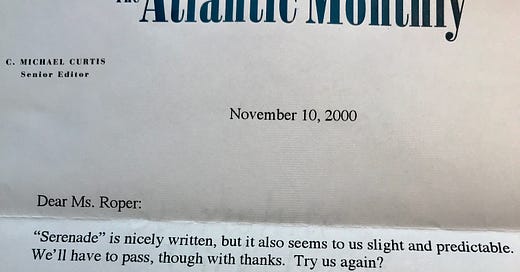

So when I opened my first SASE back from The Atlantic to find an actual, personalized, typewritten note, signed by the senior editor, C. Michael Curtis, I was gobsmacked

But then I read the note, and I felt…well, I wasn’t sure how to feel.

“Nicely written,” was decidedly condescending. I did not like that.

And “slight and predictable"—that hit me in the gut. Hard.

I wasn’t sure about the “though with thanks.” It felt like a WASPy bit of politesse. But then there was the “Try us again?” which felt completely different. With its casual tone and twinkle of a question mark, it felt genuinely kind, in a conspiratorial sort of way: We’re game if you are. What do you think?

The whole, brief thing left me feeling dizzy.

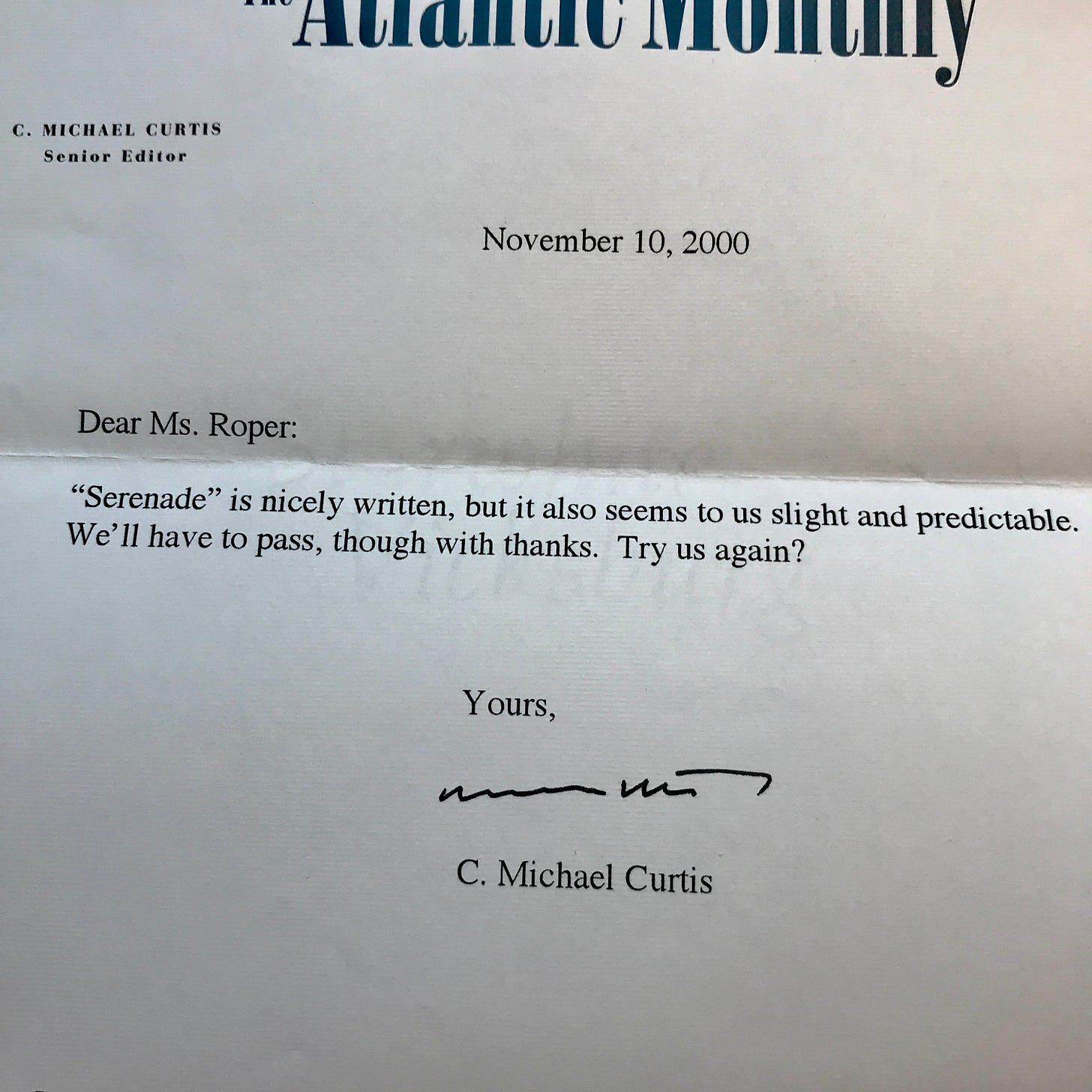

Eventually, I did submit again. And once again, I got a personal note from Curtis:

“Quite nicely written,” is markedly different from just “nicely written,” right? There’s a lifted eyebrow of approval in it.

But then came the pain. Oh the pain! I was still being predictable. Even worse (especially for a member of Gen X) sentimental. Definitely not good. And being told that your work “collapses” into anything is not what you want to hear, unless your work is a folding tray table.

But then—cue the choir of angels— “But you’re awfully good, and I hope you’ll send more.”

Cut to 28-year-old me, letter clasped to her chest (probably against some gauzy, floral baby-doll sort of top Lorelei Gilmore would wear), spinning around in ecstasy.*

AWFULLY good! Me! According to the editor of the Atlantic fucking Monthly!

Friends, I kept that “awfully good” from C. Michael Curtis in the back pocket of my mind for a very, very long time. And if a story I wrote got torn apart in workshop, or I got yet another rejection from another literary journal or agent, or something I was working on just refused to work…well, at least the editor of The Atlantic thought I was awfully good.

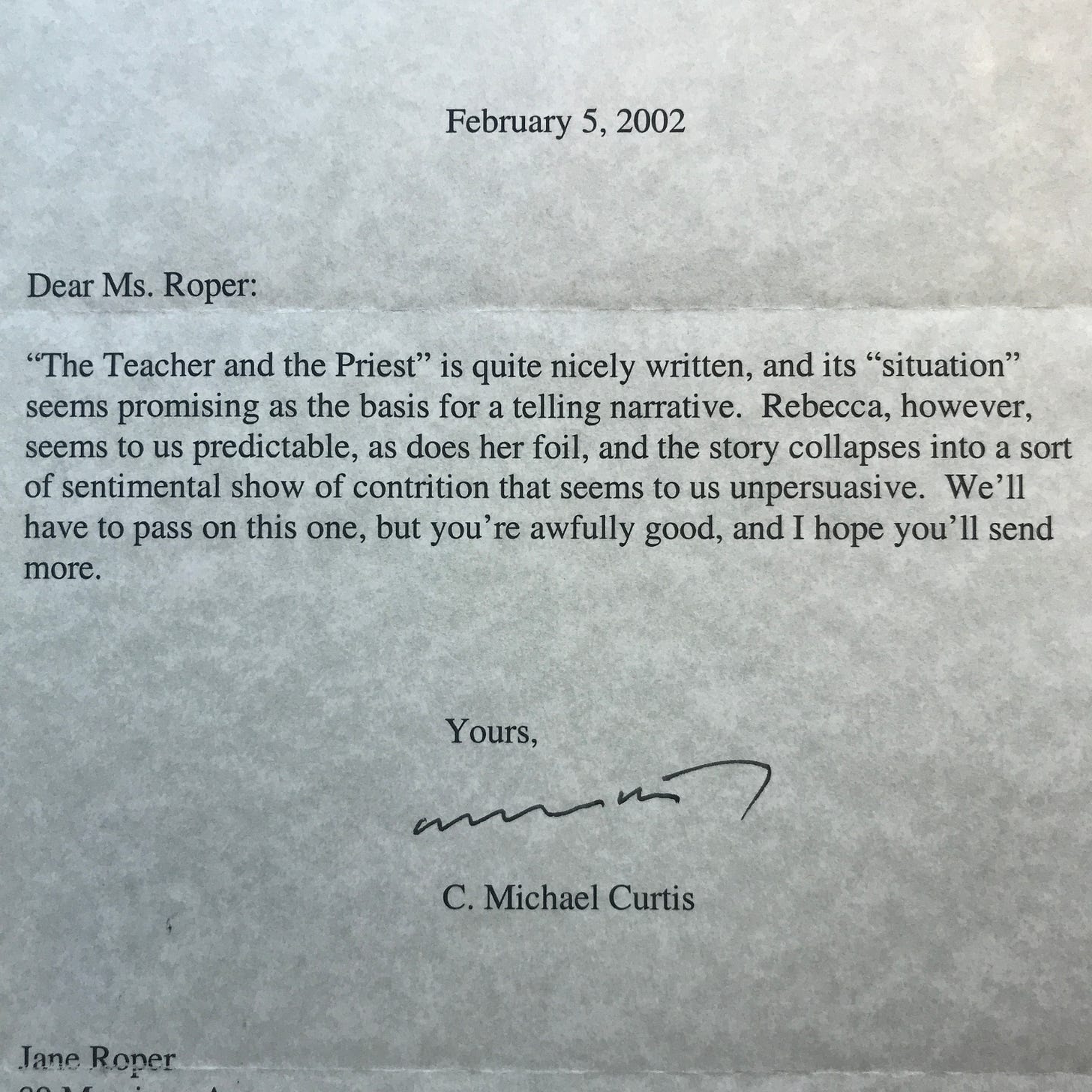

In fact, he thought it twice.

Getting the second “awfully good” didn’t pack quite the same wallop as the first, because it was clear now that he said it to all the girls it was one of his go-to phrases. Still, it was a very nice antidote to being told my story had no depth.

(Aside: Wouldn’t it be funny if I learned somehow that when Curtis told people they were ‘awfully good’ it was, like, a code, and he actually meant they were awful at BEING good? As in, they weren’t good? At all? And here I’ve been, like Dumbo with a feather in his trunk all these years.)

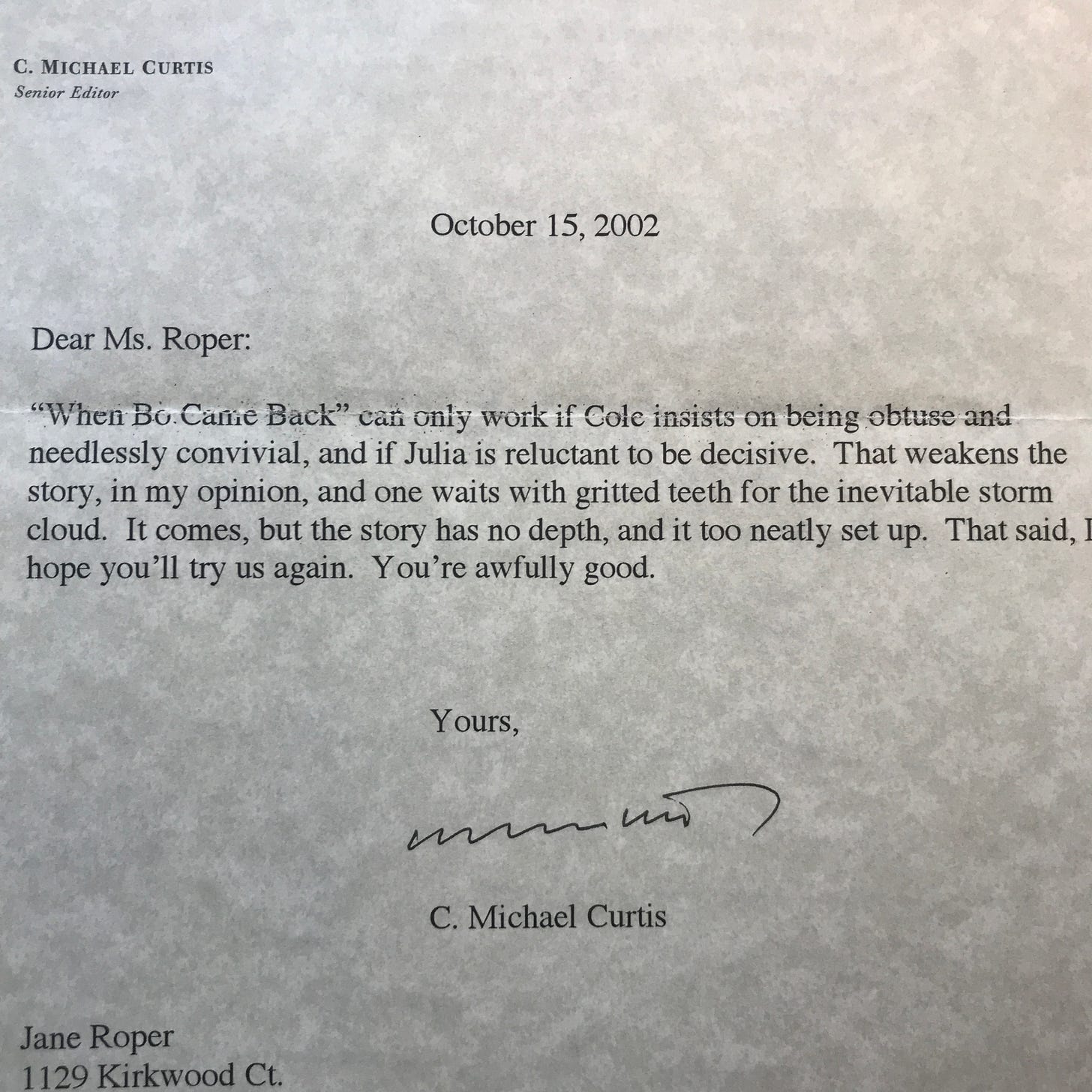

Looking back at those notes now, more than twenty years later, having no attachment to the stories I’d sent and much improved confidence in my abilities (not to mention much improved abilities, I should hope), I admire them so much.

It’s clear that Michael Curtis, like any good editor or teacher of writing, was committed to evaluating the thing—the story—separately from its maker. Either the story worked or it didn’t, in his estimation, and he would tell you exactly why. He didn’t pull punches, because it wasn’t personal.

What was personal, and what Curtis handled with such gentleness and respect, was the writer’s potential to create something that would work.

My stories were slight, predictable, sentimental, lacking depth, and prone to collapse. But apparently he saw something in them—maybe the rhythm of sentences, or the descriptions, or the dialogue, who knows—that suggested to him I had a bit of talent. And that someday I might actually manage to write something good.

I know that he gave this same gift to a lot of writers, many of whom are sharing their own personal-notes-from-C.Michael-Curtis reminiscences elsewhere right now. And I know that we’re all grateful.

He will be missed.

*Figuratively speaking. I did not actually whirl around in ecstasy. I don’t think.

P.S. Speaking of whirling around in ecstasy, look at this! (Don’t wake me up. DON’T!!)

Back when rejection letters were written on paper (or written at all!), I once papered a closet door with them.

You give me such hope, Dear Jane...and you're awfully good at it. <3